" . . . Always try to associate yourself closely with and learn as much as you can from those who know more than you, who do better than you, who see more clearly than you. Don't be afraid to reach upward. Apart from the rewards of friendship, the association might pay off at some unforeseen time -- that is only an accidental by-product. The important thing is that the learning will make you a better person."

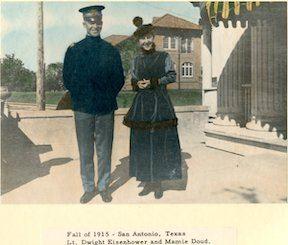

It was mid-September 1915, when Second Lieutenant Dwight D. Eisenhower left Abilene to join the 19th Infantry at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. In the next three and one-half years, he would serve at eight different military posts, marry, become a father, and experience the Great War from stateside.

Texas

For troops stationed at "Ft. Sam" in 1915, there was far more concern about conflict with Mexico than the war that consumed Europe. President Wilson proclaimed that he would keep the United States out of war, and most Americans supported that policy. But, by the winter of 1915-16, criticism of President Wilson became more vocal. Some citizens were becoming impatient with his cautious reaction to Germany’s submarine warfare and Pancho Villa’s guerrilla warfare along the border.

With the entry of the United States into World War I, Ike was ordered to Leon Springs, Texas, to set up a training camp. From there he was assigned to train officers at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, and Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Next, he helped to create the first tank training school at Camp Meade, Maryland. Finally, he assisted in organizing the first official tank corps at Camp Colt, near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. After the armistice, he accompanied his troops first to Camp Dix, New Jersey, and then on to Fort Benning, Georgia, before returning to duty at Camp Meade in March 1919.

Through this period, Ike’s superiors recognized his genius for managing big projects with painstaking attention to detail. In turn, he was placed in positions of leadership and given much responsibility. He learned about effective training methods, army administration, and organization and planning on a large scale. Working under a variety of commanding officers exposed him to various personality types and leadership styles. Because Ike worked very hard to do his very best whether he liked the job or not, he was building an enviable reputation among his superior officers. In fact, his performance at Camp Colt so impressed his commanding officer that Ike was recommended for the Distinguished Service Medal, which he later received.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1916

Soldiers and officers who trained under Ike respected and admired him. Although a demanding and strict disciplinarian, he was scrupulously fair. His overriding objective was to prepare his troops for what they would meet in the trenches of France. Often he was frustrated in his efforts to get proper equipment and supplies for his men. From these experiences, he learned how to improvise and find creative ways to get what he needed. He was conscientious to a fault and applied such intensity to this job that he often worked far beyond the point of exhaustion. When he delivered his men to the ships that would transport them across the Atlantic, not one was turned back for any reason. He had done his job well, perhaps too well, because the top brass of the army now knew that it could not afford to lose this officer to the bloodbath of the Western Front.

Ike ached to receive orders for active duty. Leadership in battle was all that he had trained for, and he found it impossible to wait patiently. To his extreme frustration, many of his West Point classmates were already in France. Time and again his superior officer promised him that he would accompany his men overseas, only to rescind the order at the last minute. Another promotion did little to lessen the disappointment. Despite his nearly constant frustration, however, Ike continued to carry out his duties to the best of his ability.

When orders came through that he would ship out with his men on November 18, 1918, he was euphoric! But, when word came of the Armistice on November 11, 1918, it seemed that all the earth had conspired to thwart his dreams. He had missed his war, and he could scarcely bear the bitterness of it.

“Some of my class were already in France. Others were ready to depart. I seemed embedded in the monotony and unsought safety of the Zone of the Interior. I could see myself, years later, silent at class reunions while others reminisced of battle For a man who likes to talk as much as I, that would have been intolerable punishment. It looked to me as if anyone who was denied the opportunity to fight might as well get out of the Army at the end of the war.”

When Ike was commissioned into the small peacetime Army of 1915, promotions were based on seniority and were few and far between. The great mobilization for World War I had changed that temporarily. As a result, Ike had risen in rank from a second lieutenant in mid-1915 to a temporary lieutenant colonel on his 28th birthday in 1918 — one of the youngest in the history of the U.S. Army. With the end of the war, the standing army shrank back to its pre-war size. Wartime Lieutenant Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower reverted to a peacetime permanent rank of major in 1924. Here he would remain for another sixteen years.

Ike and Mamie

Though often frustrated during the Great War years, Ike’s personal life had been on the whole, happy and fulfilling. On a sunny October 3rd afternoon, in 1915, he met Miss Mamie and her family, the Douds of Denver. There was an instant spark of attraction between 18-year-old Mamie and soon-to-be-25-year-old Ike. Mamie was a popular young woman who had lived a sheltered and privileged life. When Ike asked her on a date, he had to wait four weeks for her schedule of suitors to clear. In the meantime, he was a constant fixture in the Doud’s winter San Antonio home. When Mamie’s dates arrived, Ike greeted them, and when they brought her home, he met them at the door. Ike spent his time getting to know John and Elvira Carlson Doud and Mamie’s three sisters. By the time he and Mamie had their first date, Ike had already won over the rest of the Doud family.

Ike and Mamie quickly became a pair. On dates, they often went to a Mexican restaurant called “The Original,” where dinner for two was just $1.00. When Ike could afford it, they took in movies and vaudeville acts at the Orpheum Theater. On Valentine’s Day 1916, Ike and Mamie became engaged, promising the Douds they would wait to marry until after Mamie’s 20th birthday. But tensions with Mexico escalated, and, fearing that Ike would be sent to the border, they moved up the wedding. On July 1, 1916, Ike and Mamie were married in the Doud’s Denver home. Friends of the Douds whispered among themselves that, at nineteen, Mamie was too young to marry and that First Lieutenant Dwight D. Eisenhower had married above himself.

wedding day

For most of the first three years of their marriage, Mamie lived with her parents because there was no family housing available on post. When they could live together, their popular quarters was nicknamed “Club Eisenhower” — a place to play cards, listen to music, and generally have fun. Mamie was a perfect Army wife. She loved to entertain and did it well, despite the fact that she could cook little except fudge and mayonnaise. Elvira Doud had not allowed her daughters to learn to cook — that way they would never have to. Ike cooked as often as he could, and they dined frequently at restaurants.

On September 24, 1917, while Ike was living in the trenches with his men at Fort Oglethorpe, Doud Dwight Eisenhower was born in San Antonio at his grandparents’ home. John Doud was so taken with his new grandson, that he gave Mamie an allowance of $100 a month thereafter. Little “Ikky” quickly became the centerpiece of Ike and Mamie’s life. Ike’s great disappointment in being stationed stateside was tempered with the happiness he felt as a husband and father.

Ike administered the demobilization process conscientiously. He demonstrated the same care and responsibility for the men in his charge as he had when preparing them for war. Although he did not realize it yet, his performance in carrying out his duty had been noted in high places. For his part, he felt only overwhelming regret at having missed his war. As he recommitted himself to a military career, he vowed to make up for lost opportunities. He would “cut a wide swath” through the post-war, peacetime Army that would be impossible to ignore.

This content is from The Eisenhower Life Series: Duty, Honor, Country, an educational series written by Kim Barbieri for the Eisenhower Foundation, copyright 2002. Funding was provided by the Dane G. Hansen Foundation and the State of Kansas.

For a complete timeline of Dwight D. Eisenhower's life, visit the Eisenhower Interactive Timeline.

Eisenhower Foundation

Eisenhower Foundation