Preparing for the Future

In the spring of 1909, Dwight D. Eisenhower graduated from Abilene High School. That summer he worked at a series of jobs to help put his older brother, Edgar, through college. In the autumn, Dwight took a job at the Belle Springs Creamery where he worked for nearly two years.

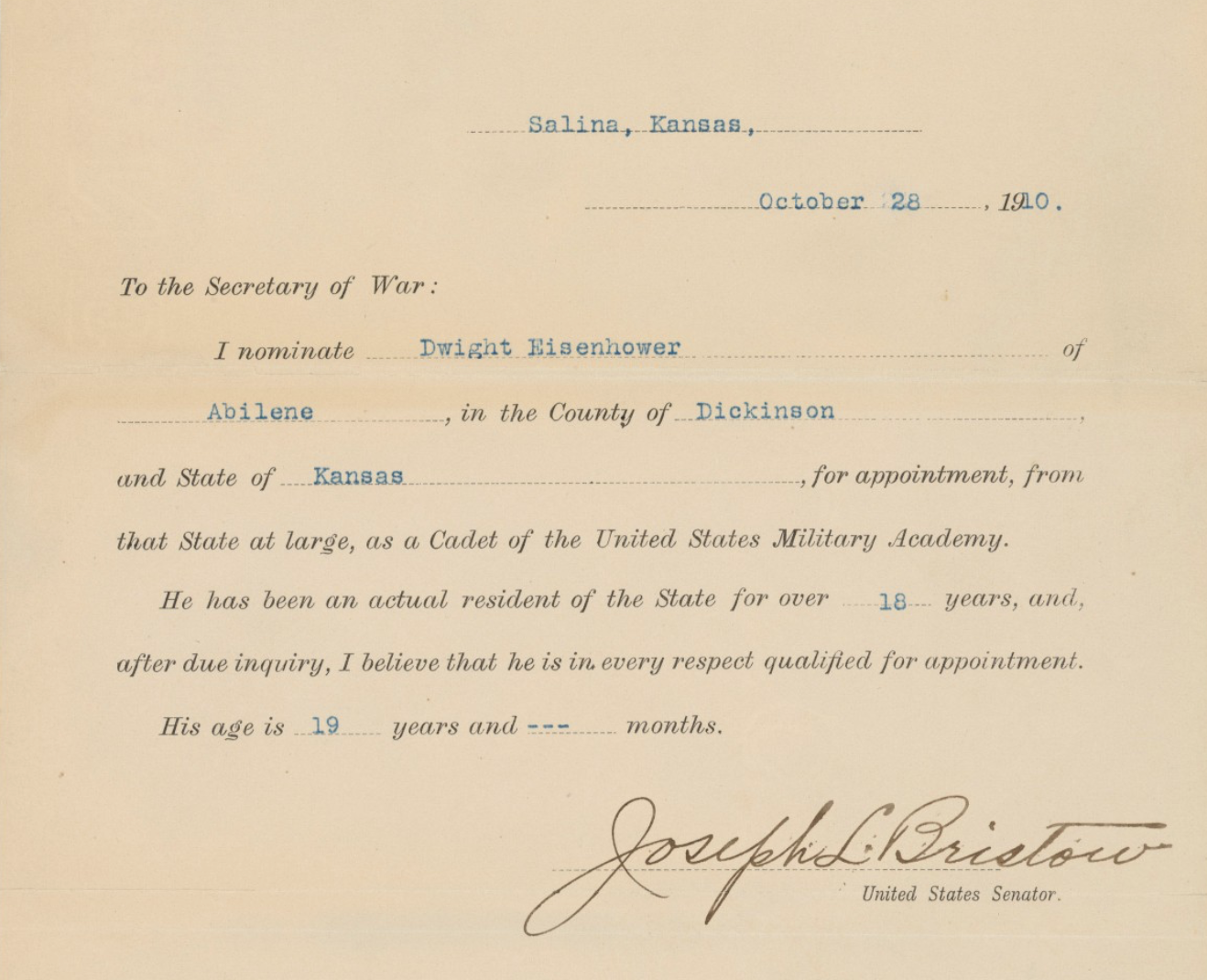

A friendship with Everett Edward “Swede” Hazlett was renewed when Swede returned to Abilene for the summer of 1910. He encouraged Dwight to apply for an appointment to the naval academy at Annapolis. On August 20, 1910, Dwight wrote a letter to a Kansas senator, Joseph W. Bristow, asking for an appointment, but received no reply. Then, when a notice for academy applications appeared in the local newspaper in early September, Dwight wrote again. This time the Senator wrote back with the information that Dwight needed to proceed.

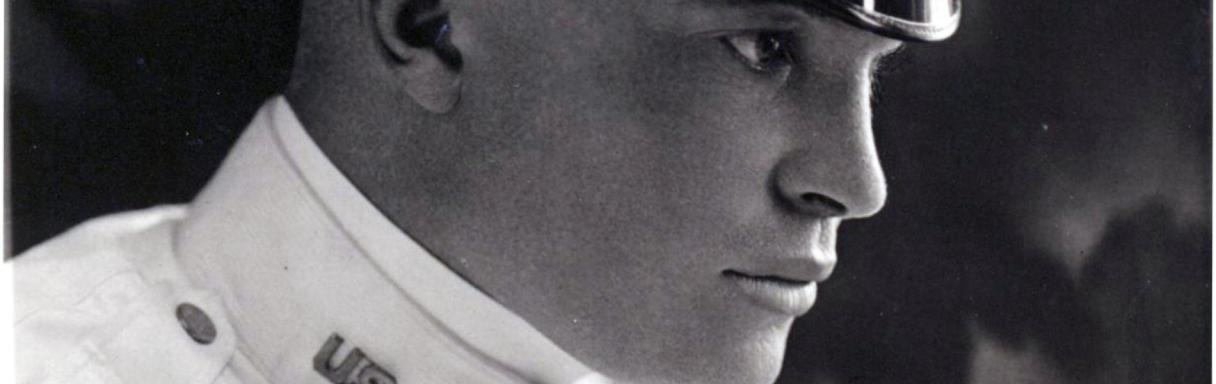

In October, Dwight traveled to Topeka, Kansas, to take Senator Bristow’s service academies exam. He placed first for Annapolis and second for West Point with an overall score of 87%. But, at age 20, Dwight was too old to be admitted to Annapolis. Although he had placed second for West Point, the letters of recommendation written for him were so impressive that Bristow awarded him the appointment anyway. In January 1911, Dwight would take the West Point entrance exams, both academic and physical.

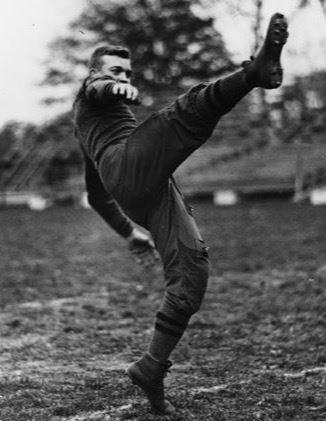

From October 1910 until January 1911, Dwight returned to Abilene High School to study for the physics, math, and chemistry portions of the test. He even played football for his old school. At night, in between duties at the creamery, he and Swede studied, snacking on ice cream and chicken roasted on a shovel in the furnace. Dwight passed his exams and was ordered to report to the United States Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, New York, by June 14, 1911.